To positively identify an Inconel alloy you should combine documentary verification (mill test report, heat number) with instrumental chemical analysis, positive material identification (PMI) using X-ray fluorescence (XRF), optical emission spectrometry (OES) or laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS), backed up by laboratory techniques (ICP-OES/ICP-MS and metallography) when absolute precision is required. Quick shop-floor checks (magnet, simple appearance) help sort suspect parts, but they cannot replace PMI or laboratory chemical analysis for conclusive identification.

Why correct identification matters

Inconel is a family of nickel-base superalloys used in high-temperature, corrosive, or mechanically demanding environments (aerospace, power generation, oil and gas, chemical plants). Using the wrong alloy can cause premature failure, regulatory noncompliance, and catastrophic incidents. For pressure-system or safety-critical components, industry rules require positive verification of alloy chemistry and traceability. API and ASTM guidance structures for material verification are widely referenced in these sectors.

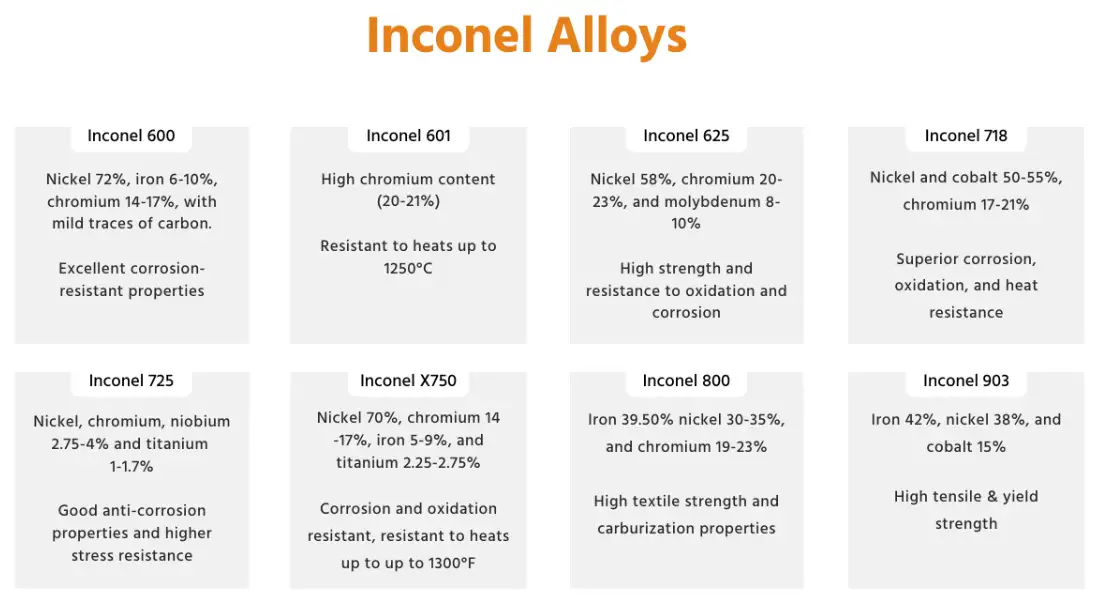

Chemical families and common Inconel grades

Inconel covers a range of nickel-chromium-based alloys. The two most frequently encountered grades in industry are Inconel 625 and Inconel 718. Below is a compact comparison of typical composition ranges and a short note on the functional role of key elements.

Table 1 — Typical (representative) composition ranges (wt%) for common Inconel grades

| Element | Inconel 600 (typical) | Inconel 625 (typical) | Inconel 718 (typical) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nickel (Ni) | 72.0–80.0 | 58.0–63.0 | 50.0–55.0 |

| Chromium (Cr) | 14.0–17.0 | 20.0–23.0 | 17.0–21.0 |

| Iron (Fe) | 6.0–10.0 | Balance | Balance (~17–21%) |

| Molybdenum (Mo) | 0 | 8.0–10.0 | 2.8–3.3 |

| Niobium (Nb)/Columbium (Cb) | 0 | 0.4–1.0 | 4.75–5.5 (as Nb + Ta) |

| Titanium (Ti) | trace | trace | 0.65–1.15 |

| Aluminum (Al) | trace | trace | 0.2–0.8 |

| Carbon (C) | ≤ 0.10 | ≤ 0.10 | 0.04–0.10 |

Source: manufacturer datasheets and material datasheets for representative ranges.

Notes:

-

718 is age-hardenable: the strength comes from niobium (Nb) and titanium precipitates (gamma prime and gamma double prime phases), which also drive specific identification signatures under metallography.

-

625 relies on solid-solution strengthening and high Mo for corrosion resistance.

Fast shop-floor checks (sorting tools and their limits)

These checks are low-cost and rapid. Use them for triage only.

Magnet test

-

What it shows: Nickel-based Inconel alloys are typically nonmagnetic in the annealed or solution-treated condition. Slight magnetism can develop after cold work or certain heat treatments. A magnet that "sticks" strongly suggests a ferrous alloy or heavily iron-bearing stainless steel; a weak or no response keeps nickel-base alloys in play.

-

Limitations: Not definitive. Some stainless steels are also nonmagnetic; some nickel alloys may show weak magnetism under certain conditions.

Visual and marking inspection

-

What it shows: Look for stamped grade/heat number, surface finish, weld marks and color. Many OEM parts carry heat numbers that link to mill test reports.

-

Limitations: Markings can be missing, worn, or falsified.

Spark test

-

What it shows: Limited. Spark testing works for sorting carbon or alloy steels because ferrous metals generate characteristic sparks.

-

Limitations: Nickel-base alloys produce little to no spark or ambiguous patterns, so this method cannot confirm Inconel. Do not rely on spark testing to prove an alloy is Inconel.

File, hardness and simple mechanical checks

-

What they show: Relative hardness or machinability can hint at alloy class.

-

Limitations: Overlap between alloys and heat treatments make these inconclusive.

Practical tip: Use shop checks to decide whether to run PMI; do not accept shop checks as positive identification for safety-critical applications.

Industry-standard nondestructive methods (PMI technologies)

Positive Material Identification (PMI) is the standard field approach to chemically verify alloy composition without cutting samples. Handheld analyzers deliver fast results that map to alloy specifications. API RP 578 and ASTM guidance are commonly used frameworks for implementing PMI programs.

X-ray fluorescence (XRF)

-

How it works: A beam of X-rays excites atoms in the sample, producing characteristic secondary X-rays that are element-specific. Handheld XRF units report elemental percentages (for many heavy elements) or identify the nearest alloy grade from a database.

-

Strengths: Portable, rapid, non-contact, excellent for heavier elements (Ni, Cr, Mo, Nb, Fe). Widely used in field PMI.

-

Limitations: Poor sensitivity for light elements (carbon, nitrogen, boron) so XRF cannot measure carbon reliably. Surface coatings, paint, or heavy oxidation can skew readings. Calibration and reference standards matter. For final certification where C-level matters, lab tests are required.

Optical emission spectrometry (OES), spark OES

-

How it works: A spark or arc excites sample atoms and emitted light is dispersed to measure elemental lines; OES quantifies a wide range of elements including carbon at reasonable detection limits.

-

Strengths: Better detection of light elements and trace alloying elements relative to XRF. Often used in shop-floor OES benches or portable OES for more exact composition.

-

Limitations: Requires surface preparation and contact; typically semi-portable but less convenient than handheld XRF.

Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS)

-

How it works: A pulsed laser ablates a tiny amount of material, producing plasma that emits light analyzed to give elemental composition, including light elements.

-

Strengths: Rapid, can detect light elements including carbon; emerging in field PMI and included in newer API guidance annexes.

-

Limitations: Newer technology; instrument cost and operator training required.

Which PMI method to choose?

-

For fast field screening and most alloy verifications, handheld XRF is the most common. For alloys where carbon or light-element quantification is critical, OES or LIBS is preferred. Always follow a documented PMI procedure and calibrate against standards.

Laboratory and destructive methods (the gold standard)

When the service is critical or the PMI result is ambiguous, send samples to a qualified laboratory.

ICP-OES / ICP-MS (wet chemistry)

-

What they deliver: High-accuracy, certified elemental analysis including trace and light elements (via appropriate digestion and preparation). Accepted as laboratory confirmation for procurement, certification or root-cause investigation.

-

Advantages: Best accuracy and detection limits for nearly every element.

-

Disadvantages: Requires sample removal (destructive), longer lead time and higher cost. Labs provide traceable certificates and uncertainty statements.

Metallography and microstructure (SEM, optical microscope, EDS)

-

Use cases: Determine heat treatment condition, precipitate structure (gamma prime, gamma double prime), grain size, presence of defects, and weld microstructure. Scanning electron microscopy with EDS gives local compositional analysis and microstructural imaging. For Inconel 718, the presence of gamma double prime and Nb-rich phases are telling signs of proper chemistry and heat treatment.

Mechanical testing

-

Tensile, hardness, creep, impact tests confirm mechanical performance consistent with the specified grade. These are sometimes required in qualification or failure analysis.

Microstructural signatures and what they mean

Metallurgists use phase and precipitate morphology to corroborate chemical analysis.

-

Inconel 718: precipitation-hardened by gamma prime (Ni3(Al,Ti)) and gamma double prime (Ni3Nb) phases that provide high strength after proper aging. A typical metallographic exam (etched and examined by optical/SEM) reveals these fine precipitates and grain structure consistent with a correctly processed 718 heat.

-

Inconel 625: lacks the same age-hardening precipitates; it relies more on solution strengthening and forms different carbides or intermetallics under extreme conditions. Metallography will therefore show a different precipitate fingerprint.

Those microstructural markers help distinguish 718 from 625 when chemical tests are borderline.

Documentation and traceability

Positive identification is not only a measurement exercise; documentation matters.

-

Mill Test Report (MTR) / Certificate of Analysis: Should include the material’s UNS number, heat number, chemical composition, and mechanical tests. Use MTR to cross-check PMI or lab measurements.

-

Heat number verification: Mill or manufacturer trace of production batch linking the part to an MTR. For procured components, accepting only items with complete MTRs prevents mix-ups.

-

Recordkeeping: PMI logs, calibration dates of instruments, inspector qualifications and photographs should be stored per customer or regulatory requirements (API RP 578 suggests record elements).

Common misidentifications and traps

-

Assuming nonmagnetic = Inconel. Several austenitic stainless steels are also nonmagnetic.

-

Relying on surface color or appearance. Oxide scale, plating, machining marks or contamination produce misleading visual cues.

-

Taking XRF carbon numbers at face value. XRF does not reliably measure carbon; when carbon matters (welding, heat treatment), use OES or lab analyses.

Recommended field + lab workflow (practical step-by-step)

-

Document: photograph part, record markings, heat number, location, and serial.

-

Triage checks: magnet test, dimensional verification, visible welds or coatings.

-

PMI (first pass): handheld XRF over multiple points, record results and instrument calibration certificate. If XRF matches declared alloy composition within project tolerance, flag passed for initial verification.

-

If XRF ambiguous or carbon/trace elements required: perform portable OES or LIBS on cleaned surface.

-

If any doubt remains or critical service: cut sample and send to accredited laboratory for ICP-OES / ICP-MS plus metallography. Obtain certified analysis with uncertainty.

-

Record: keep PMI certificates, lab reports, and link results to the part’s heat number and MTR.

Comparison tables

Table 2 — Methods comparison: speed, typical accuracy, and sample damage

| Method | Typical field speed | Typical accuracy (major elements) | Detects C? | Sample damage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Handheld XRF | seconds per spot | ±0.1–0.5 wt% for heavy elements (varies) | No | None |

| Portable OES | seconds–minutes per spot | ±0.05–0.2 wt% for many elements | Yes (can measure C) | Minimal (contact spark) |

| LIBS (portable) | seconds | Comparable to OES for many elements | Yes | Microscopic ablation |

| ICP-OES / ICP-MS (lab) | days turnaround | high-accuracy, trace-level | Yes | Destructive sample prep |

| Metallography (SEM/EDS) | days | local composition, microstructure | N/A | Destructive sample mount |

Use the table to pick the right tool for risk level and element needs.

Table 3 — Typical signatures used for distinguishing 718 vs 625

| Feature | Inconel 718 | Inconel 625 |

|---|---|---|

| Nb (niobium) | High (~4.75–5.5%) | Low (≤1%) |

| Mo (molybdenum) | ~3% | ~8–10% |

| Precipitate structure | Gamma prime and gamma double prime (age-hardened) | No gamma double prime; carbides or other phases possible |

| Common uses | Rotating parts, high-strength fasteners, aerospace | Corrosion-resistant piping, chemical equipment |

Chemical ratios (Nb, Mo) are decisive in lab or PMI readings.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What single test proves a part is Inconel?

A single, definitive proof requires accurate chemical analysis showing the alloy’s characteristic composition together with traceable documentation (MTR/heat number). In practice, PMI (XRF + OES or LIBS) plus an MTR is accepted for most industrial needs; for final proof, lab ICP analysis and metallography provide certification.

2. Can a magnet identify Inconel?

No. Magnet testing only helps separate ferrous from nonferrous material. Inconel is generally nonmagnetic but that trait is not unique. Some nickel alloys show weak magnetism after cold work, so magnet results are inconclusive for identification.

3. Is handheld XRF enough for procurement acceptance?

Handheld XRF is widely used for PMI and accepted for many projects, provided instruments are calibrated, procedures documented and the buyer accepts XRF limitations (notably carbon). For critical service, supplement XRF with OES or lab analysis.

4. Why can’t XRF measure carbon?

XRF instruments detect the X-ray lines of heavier elements; the light element K and L lines for carbon are outside the practical detection window for most handheld XRF analyzers. Use OES or lab methods for carbon.

5. What is the difference between OES and LIBS?

Both are optical emission methods. OES uses an electrical spark to vaporize material; LIBS uses a laser pulse. LIBS is gaining ground for field use because it can detect a wider element range rapidly, but operator training and instrument selection are important.

6. Can I rely on the part stamping?

Prefer not to rely only on stamping. Heat numbers and MTRs must be verified; stamps can be incorrect or added later. Combine stamping with PMI and MTR review.

7. How many PMI points should I test on a component?

API and best-practice documents recommend multiple test points to cover welds, parent material and potential mixing. The exact number depends on part size and criticality; record locations and results.

8. What acceptance tolerances are typical for PMI?

Acceptance tolerances are project-specific. API RP 578 suggests typical tolerances for major elements; many projects use ±5–10% of the nominal composition for field verification. Use contract or code requirements to set tolerances.

9. Can metallography identify Inconel grade?

Metallography reveals heat treatment and precipitate signatures that support identification (718’s gamma double prime, for example). It complements chemical analysis but cannot replace chemical assays.

10. If PMI fails, what next?

If PMI yields unexpected chemistry, quarantine the part, notify quality and project engineering, obtain laboratory confirmation (ICP and metallography), and trace MTRs and supplier paperwork to resolve mismatch.

Practical examples and quick scenarios

-

Field example 1 — suspect turbine fastener: magnet weak; XRF shows Ni ~52%, Cr ~19%, Nb ~5.0% → consistent with 718; follow with OES or lab sample to confirm carbon and microstructure when component is critical.

-

Field example 2 — pipe spool labeled 625: XRF shows Ni ~60%, Cr ~22%, Mo ~9% → consistent with 625; if MTR is present and welds match chemical profile, accept for corrosion service. If carbon content is a weldability concern, run OES or lab test.

Quick reference: PMI best-practice reminders

-

Calibrate instruments daily against certified reference materials.

-

Clean the test surface of paint, heavy oxides, or plating before measurement.

-

Use multiple test points and log them.

-

Maintain instrument calibration certificates and operator training records.

-

For safety-critical items, require lab confirmation and traceable MTRs.

Closing summary

Shop checks speed up decision-making; the industry relies on PMI for on-site verification; laboratory methods give definitive proof and microstructural context. For procurement, certification and safety, combine documentation (MTR) with analytical methods: XRF for heavy elements, OES/LIBS for light elements and carbon, and ICP/metallography for final certification. Follow API RP 578 and ASTM E1476 guidance in setting procedures and records.