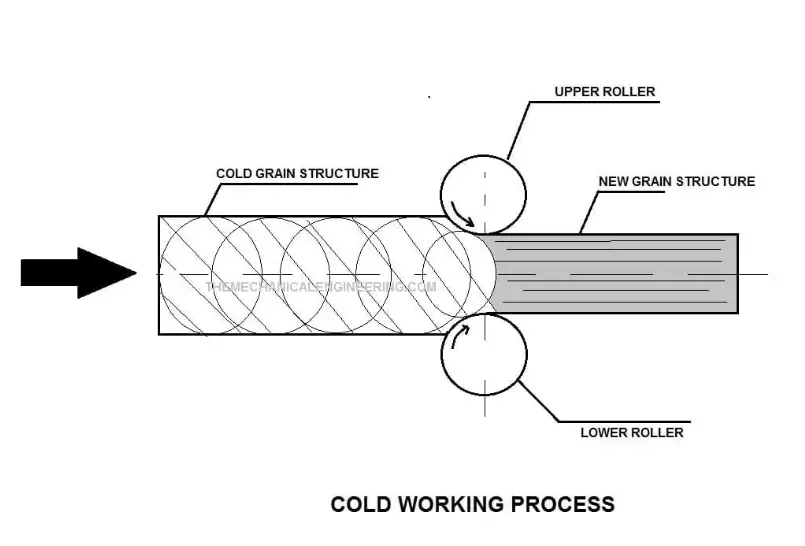

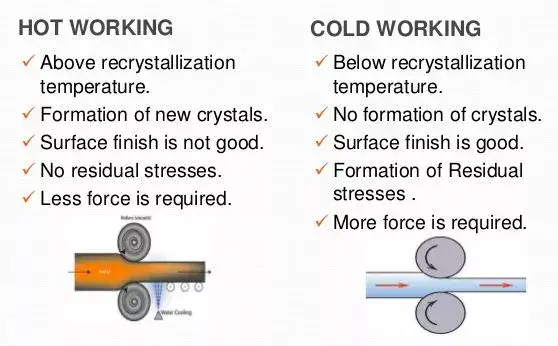

Cold working is the controlled plastic deformation of metal at temperatures below its recrystallization range; this process increases strength and hardness through strain hardening while reducing ductility and altering microstructure and residual stress. When used correctly, cold working delivers tight dimensional control, superior surface finish, and improved mechanical performance for finished parts. Effective application requires selection of appropriate processes, tooling, lubrication, and, when needed, post-deformation heat treatment to restore formability or relieve stress.

What Is Cold Working and brief history

Cold working, sometimes called cold forming or strain hardening, refers to metal shaping done at temperatures below the material's recrystallization temperature. The technique has roots in early metalworking where craftsmen shaped metals by hammering, progressing into modern industrial processes such as cold rolling, drawing, stamping, and cold forging. Industrial adoption accelerated with improvements in dies, presses, and lubrication which permitted high-volume production of precise components.

Modern metallurgical study explains why cold working strengthens metals and why tradeoffs in ductility and residual stress arise. Key literature from metallurgical societies provides tested relationships between the degree of deformation and property change.

Fundamental mechanisms: what happens inside the metal

Dislocations and strain hardening

Plastic deformation in crystalline metals proceeds by dislocation motion on crystallographic slip systems. When a metal is deformed at low temperature, dislocation density rises. Increased density causes dislocations to interact and obstruct each other, raising the stress required for further plastic flow. This phenomenon produces higher yield strength and greater hardness. The stored energy in the deformed lattice also lowers the temperature required for recrystallization if a subsequent heat treatment is applied.

Texture, anisotropy, and grain distortion

Cold working tends to elongate grains and produce crystallographic texture aligned with deformation direction. This results in anisotropic mechanical response: a part may yield differently when loaded in the rolling or drawing direction than when loaded transverse to it. Control of texture is critical for parts that must perform under multi-axial loads.

Residual stresses and their influence

Plastic flow is rarely uniform through thickness, which leads to residual stress fields after unloading. Tensile residual stress near a surface can significantly reduce fatigue life and increase susceptibility to certain corrosion cracking mechanisms. Compressive residual stress at the surface can improve fatigue resistance. Engineers must measure and manage residual stress using process design, stress-relief heat treatment, or surface treatments.

Common cold working processes and where each fits

Below is a practical list of widely used cold forming methods, each with typical applications.

Table 1: Cold working processes, principal mechanics, and common applications

| Process | Principal mechanics | Typical materials | Typical uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cold rolling | Passing stock between rollers to reduce thickness | Stainless, carbon steel, aluminum, copper | Sheet and strip production, precision gauges |

| Cold drawing | Pulling bar, wire, or tube through a die | Steel wire, copper, aluminum | Wire, rod, precision shafts, seamless tubing |

| Stamping and blanking | Shearing and forming sheet with dies | Low to medium carbon steel, stainless | Automotive panels, brackets, enclosures |

| Bending (press-brake, roll forming) | Plastic bending about a radius | Steel, aluminum | Structural channel, profiles, frames |

| Coining and fine blanking | High-pressure forming for surface detail | Soft steels, copper alloys | Coins, high-precision parts |

| Cold forging | High-strain forming in dies while cold | Carbon and alloy steels, stainless | Fasteners, gears, high-volume automotive parts |

| Roll forming | Continuous bending using a sequence of rollers | Carbon steel -> galvanized sheet | Long lengths of profiles, roofing, framing |

Sources indicate broad industrial uptake of these techniques, plus significant optimization literature for process parameters.

How cold work changes properties and microstructure

Mechanical property trends

General trends following cold working include:

-

Yield and tensile strength increase because of dislocation accumulation

-

Hardness rises with increased plastic strain

-

Ductility and elongation fall with continued work hardening

-

Toughness often decreases, particularly for high-strain regions

Quantitative change depends on alloy chemistry, initial temper, and percent cold work. For many common metals, a modest percent cold work (for example 5–20 percent reduction in area) raises strength noticeably while preserving acceptable ductility for forming or finishing. Larger reductions produce proportionally larger strength increases but may demand intermediate anneals.

Electrical and thermal properties

Electrical conductivity typically falls after cold work because increased dislocation density scatters conduction electrons. Thermal conductivity may be affected as well, often declining with heavy deformation. For applications that depend on conductivity, designers must factor in any cold work steps.

Corrosion and fracture behaviors

Cold work alters electrochemical behavior in some alloys. In ferrous alloys under sour conditions, cold deformation increases risk of stress corrosion cracking or sulphide stress cracking. Data support limits on percent cold work for components destined for sour environments, with conservative practice suggesting heat treatment after significant cold deformation.

Measurement, metrics, and practical limits

Percent cold work and strain metrics

Percent cold work is often reported using thickness or area reduction metrics for sheet and wire. True strain and engineering strain provide precise descriptions for design and numerical simulation. Typical notation:

-

Percent cold work by thickness = 100 × (t0 − tf) / t0

-

For drawing and rolling, cumulative true strain may be used for process control and recrystallization prediction.

Forming limit curves and fracture prediction

Forming limit diagrams help determine the maximum local strains that sheet metal can sustain without necking or cracking. Cold forming processes must remain inside safe zones defined by tests for the specific alloy and temper.

Practical process ceilings

Cold working is limited by the material's cold formability and machine capacity. Stainless steels and high-strength alloys often permit less cold reduction before cracking. For high-strength steels, intermediate anneals at controlled temperatures restore ductility for additional forming steps.

Tooling, lubrication, and process control

Tool material and surface finish

Tool steels and carbide are common for dies and punches. Tool surface finish controls friction and final surface quality. Polishing and coatings such as PVD or nitriding extend tool life.

Lubrication strategy

Appropriate lubricants reduce frictional heating and protect surface finish. Selection depends on process temperature, contact pressure, and part geometry. For high-volume cold forging, semi-solid lubricants with graphite or phosphates may be used, followed by cleaning and coating steps.

Process monitoring

Key variables to monitor include force-stroke profiles, power consumption, part dimensions, and surface integrity. Inline measurement and SPC (statistical process control) maintain consistency. Finite element models often predict strain distribution and aid die design.

Failure modes linked to cold working and inspection methods

Typical failure modes

-

Cracking during forming due to excessive local strain

-

Springback causing dimensional nonconformity

-

Surface scoring or galling from poor lubrication

-

Fatigue initiation from tensile residual stress at surfaces

-

Reduced corrosion resistance or stress corrosion cracking in certain environments

Inspection methods

-

Visual and tactile inspection for surface defects

-

Microhardness mapping to quantify local strain hardening

-

X-ray diffraction for residual stress measurement

-

Metallographic sectioning to evaluate grain deformation and damage

-

Non-destructive methods like ultrasonic testing for subsurface defects

Heat treatment pathways after cold work

Recovery, recrystallization, and grain growth

Heat treatments used after cold work typically aim to recover ductility and remove unwanted residual stress. Steps include:

-

Recovery at lower temperatures to reduce residual stress while preserving some strain hardening

-

Recrystallization annealing at higher temperature to form new, strain-free grains and restore ductility

-

Controlled grain growth management to avoid excessive coarsening

Choice of temperature and time depends on alloy chemistry and the degree of prior cold work. ASM handbooks summarize guidelines for steel, aluminum, and copper alloys.

When to avoid annealing

In parts where strength introduced by cold work is required in the final condition, annealing might be omitted or limited to recovery cycles that do not fully remove strengthening.

Standards, testing, and specification points

Industry standards document testing protocols, dimensional and mechanical acceptance criteria, and specific test methods that apply to cold-worked parts. Common references include:

-

Standard test methods for tensile testing used to quantify strength and ductility after cold working. ASTM E8 is often referenced for metallic tensile testing.

-

ISO standards that define qualification and testing procedures for components that may have been cold formed. ISO catalog pages give official scopes for many standards.

When writing specifications, include:

-

Material grade and temper before cold work

-

Maximum allowed percent cold work or minimum retained ductility

-

Required mechanical properties after forming

-

Required post-forming heat treatment and acceptance tests

-

Surface finish and dimensional tolerance table

Design recommendations and manufacturability checklist

Practical checklist for engineers who plan cold working operations:

-

Confirm alloy cold formability with vendor data or forming trials.

-

Model forming strains using finite element analysis to predict thinning, springback, and risk zones.

-

Specify lubrication, die material, and coating to minimize friction and wear.

-

Set inspection points for hardness, microstructure, and residual stress where critical.

-

If part must tolerate sour service or cyclic loading, limit cold work or include stress-relief heat treatment.

Tables: quantitative snapshots

Table 2: Typical mechanical changes after moderate cold work (representative values; use supplier data for design)

| Material | Typical initial temper | Typical percent cold work | Approx. tensile strength change | Typical ductility change (elongation) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copper (electrolytic annealed) | Soft annealed | 10–30% | +20 to +60% | −20 to −60% relative |

| Aluminum 6061 | T4 | 5–15% | +10 to +40% | −10 to −40% |

| Low carbon steel | Hot-rolled annealed | 5–20% | +15 to +80% | −10 to −50% |

| Austenitic stainless | Annealed | 5–15% | +10 to +40% | −5 to −30% |

Note: Values above are approximate and depend heavily on alloy chemistry and processing history. Use precise test data for final specifications.

Table 3: Quick selection guide for cold forming vs hot forming

| Design driver | Cold forming favored when | Hot forming preferred when |

|---|---|---|

| Dimensional precision | Tight tolerances required | Large shape changes with less precision |

| Surface finish | High-quality surface required | Surface scale acceptable or removed later |

| Strength increase | Final part should be hardened by deformation | Need uniform properties without strain hardening |

| Part complexity | Repeated small deformations feasible | Very large deformations and shape change needed |

FAQs

-

What temperature defines cold working?

Cold working occurs below the recrystallization temperature for the alloy. For most steels, room temperature qualifies. For high-temperature alloys, the upper limit is lower, so check alloy-specific recrystallization data. -

Can stainless steel be cold worked?

Yes. Austenitic stainless steels are highly formable at low temperature, and cold work increases strength dramatically, though work hardening may complicate forming sequences. -

How does cold working affect fatigue life?

Surface tensile residual stresses introduced by uneven deformation reduce fatigue life. Conversely, process choices that produce compressive surface stresses can improve fatigue resistance. Residual stress measurement is critical for high-cycle applications. -

When must I anneal after cold work?

Anneal when additional forming steps require recovered ductility or when service requires removal of tensile residual stress. For environments prone to stress corrosion cracking, anneal if cold work exceeds conservative thresholds. -

Is cold forming cheaper than machining?

Cold forming often yields lower cost per part at scale because material usage is efficient and cycle times are fast. Tooling investment is higher, so economics depend on volume. Finite element process optimization reduces trial-and-error costs. -

How to prevent cracking in high-strength alloys when cold forming?

Use incremental forming steps with interpass annealing, reduce local strains using optimized die geometry, and use lubricants that reduce friction concentration. Material preselection and heat treatment planning are key. -

What inspection should follow a major cold forming step?

Perform dimensional verification, hardness testing, metallography for microstructure, and, where necessary, residual stress measurement via X-ray diffraction or hole-drilling. -

Does cold work change plating or coating performance?

Yes. Increased surface hardness and modified surface energy can affect adhesion and coating uniformity. Pre-plating surface treatments may need adjustment. -

Can cold working be used to strengthen wires and bars without heat treatment?

Yes. Cold drawing and cold rolling are commonly used to increase strength of wires, rods, and strips without subsequent heat treatment. -

How to predict recrystallization temperature after heavy cold work?

Recrystallization temperature typically decreases with increasing stored energy from cold work. Use alloy-specific charts or small-scale lab anneals to find the temperature-time window that restores desired properties. ASM sources provide guidance by alloy.

Practical case notes and examples

-

Automotive body panels: produced by successive stamping and forming steps on cold rolled steel. Control of springback and surface finish is critical. Simulation tools model forming and forming limit curves must be used.

-

Fasteners: cold forging produces high-strength parts with good grain flow. Cold work strengthens the shank, often removing need for quench and temper. Tooling life and lubrication dominate process economics.

-

Electrical conductors: wire drawing increases tensile strength while lowering conductivity. For certain applications, a balance is necessary between mechanical performance and electrical performance.

Key takeaways for engineering teams

-

Cold working produces stronger, harder parts through dislocation accumulation but lowers ductility.

-

Process selection should balance final mechanical targets, dimensional tolerance needs, and downstream operations.

-

Heat treatments can recover ductility when required, but they remove the strengthening benefit if full recrystallization occurs.

-

Standards and test methods must be specified explicitly in purchase documents; tensile test and forming limit data are often decisive.