Metal alloys form the backbone of modern engineering and manufacturing. A carefully selected alloy can dramatically improve strength, toughness, wear resistance, corrosion behavior, thermal stability or electrical performance compared with the base metal. For general engineering applications, steels (carbon and alloy steels) and common nonferrous alloys (aluminum, copper, nickel and titanium families) cover the majority of needs; high-performance sectors depend on superalloys, titanium alloys and specialty refractory or precious-metal alloys. Proper alloy selection must match mechanical requirements, environmental exposure, fabrication route and regulatory standards.

1. What is an alloy — definition and naming conventions

An alloy is a metallic material made by combining two or more chemical elements, of which at least one is a metal. The intended outcome is a material that shows properties different from the pure constituent metals, typically improved mechanical or environmental performance. Commercial alloys are named by traditional names (brass, bronze), by standardized codes (AISI, SAE, UNS, EN), or by proprietary trade names. Clear specification of alloy composition, temper/heat-treatment and product form is essential for repeatable performance.

Nomenclature systems commonly used

-

AISI/SAE numeric codes for steels and iron-based alloys (for historical and industrial usage).

-

UNS (Unified Numbering System) for general metals and alloys where an alphanumeric code links to chemistry ranges.

-

EN (European Norm) numbers and ISO designations in international trade.

-

Trade or proprietary names for specialized alloys (e.g., Inconel, Hastelloy, Monel).

2. Broad classification: ferrous vs nonferrous

Materials are usually split into two high-level groups: ferrous alloys (contain iron as primary constituent) and nonferrous alloys (do not contain iron as the primary metal). This classification drives magnetic behavior, typical properties and common applications. Ferrous alloys include carbon steels, alloy steels, tool steels, stainless steels and cast irons. Nonferrous alloys cover aluminum, copper, nickel, titanium, magnesium, lead, precious-metal alloys and many specialty systems.

Key practical implications:

-

Ferrous alloys are generally higher in strength and lower in cost for structural use; many require corrosion protection in exposed environments.

-

Nonferrous alloys often provide better corrosion resistance, lower density or greater electrical/thermal conductivity.

-

Many engineering choices boil down to trade-offs among mass, strength, corrosion resistance and cost.

3. Major alloy families — summary, characteristics and common grades

3.1 Carbon steels and alloy steels (ferrous)

-

What they are: Iron-carbon alloys with controlled amounts of other elements (Mn, Si, Cr, Ni, Mo, V, etc.) to set strength and toughness.

-

Common uses: Structural members, pipelines, fasteners, machine components.

-

Representative grades: A36 (structural), 1018 (low-carbon), 4140 (chromium-molybdenum alloy steel).

-

Notes: Heat treatment (quenching and tempering) is used to tune hardness and toughness.

3.2 Stainless steels (ferrous, corrosion-resistant)

-

What they are: Iron-chromium(-nickel, molybdenum, nitrogen, etc.) alloys with minimum chromium typically above ~11% to form a passive oxide. Typical sub-families: austenitic, ferritic, martensitic, duplex and precipitation-hardening stainless steels.

-

Representative grades: 304 (austenitic general purpose), 316 (austenitic with molybdenum for marine resistance), 430 (ferritic), 17-4 PH (precipitation hardening).

-

Practical note: 300-series contains nickel and offers superior corrosion resistance; 400-series typically contains less nickel and higher carbon, with different mechanical/corrosion behavior.

3.3 Cast irons (ferrous, high-carbon)

-

What they are: Iron-carbon-silicon alloys with higher carbon (>2%) than steels; types include grey, ductile (nodular), white and malleable cast irons.

-

Uses: Engine blocks, pipe fittings, heavy machine bases; ductile iron combines castability with improved tensile strength and ductility.

3.4 Aluminum alloys (nonferrous, lightweight)

-

What they are: Al-based alloys alloyed with Mg, Si, Cu, Zn, Mn among others. Widely used tempers and series include 2000, 3000, 4000, 5000, 6000 and 7000 series.

-

Representative grades: 6061 (Al-Mg-Si, general-purpose structural), 7075 (Al-Zn-Mg, aerospace high strength).

-

Uses: Transportation, aerospace, packaging, heat exchangers.

-

Standards: Several ASTM specifications control chemistry and mechanical properties for sheet, plate and extrusions.

3.5 Copper alloys (brass, bronze, cupronickel)

-

What they are: Copper base with Zn (brass), Sn (bronze), Ni (cupronickel) and other additions to tune properties. Good electrical/thermal conductivity, corrosion resistance in many environments.

-

Representative grades: C11000 (electrolytic copper), C36000 (free-machining brass), CuNi 90/10 (marine cupronickel).

3.6 Nickel-base alloys and superalloys

-

What they are: Nickel-rich systems alloyed with Cr, Co, Al, Ti, Mo and refractory elements. Engineered for high-temperature strength and oxidation resistance.

-

Representative alloys: Inconel 625, Inconel 718, Hastelloy X, Rene alloys.

-

Applications: Jet engines, gas turbines, high-temperature chemical processing.

3.7 Titanium alloys

-

What they are: Titanium with Al, V, Mo and other elements to produce high strength-to-weight and excellent corrosion resistance; notable for biocompatibility.

-

Representative grades: Ti-6Al-4V (widely used aerospace and medical grade).

-

Uses: Aerospace structures, medical implants, corrosive service.

3.8 Magnesium alloys

-

What they are: Very low density metals alloyed with Al, Zn, Mn for light structural applications where weight is critical.

-

Uses: Automotive, aerospace secondary structures, electronics housings.

3.9 Lead, tin and specialty low-melting alloys

-

What they are: Soft or low-melting alloys used for bearings (Babbitt), solders (tin-lead, lead-free), shielding and radiation applications (lead-base).

-

Environmental note: Many lead-containing alloys face regulatory restrictions; lead-free solders are common in electronics.

3.10 Precious metal and coinage alloys

-

What they are: Gold, silver and platinum group alloys used for jewelry, electronics contacts and catalysis. Sterling silver and crown gold are examples.

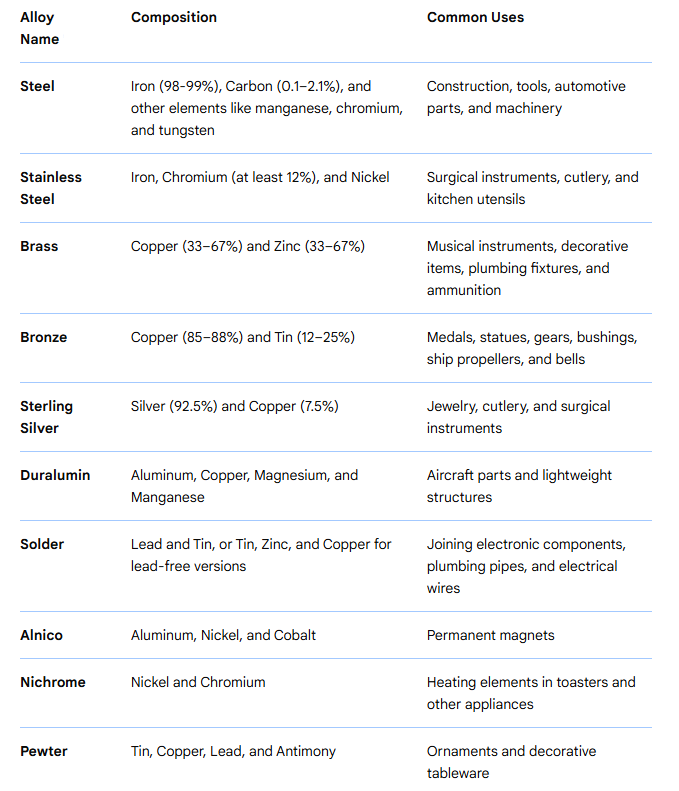

4. Typical chemical compositions and quick-reference property tables

Below are compact, practical tables intended for quick comparison. Percent ranges are indicative; exact specifications depend on the chosen grade and standard.

Table 1: High-level alloy family comparison

| Alloy family | Typical base elements | Key strengths | Typical density (g/cm³) | Typical uses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon steel | Fe + C + Mn | Low cost, high strength after heat treat | 7.85 | Structural, machinery |

| Stainless steel | Fe + Cr (+Ni, Mo) | Corrosion resistance, formability | 7.7–8.0 | Food, medical, marine |

| Aluminum alloys | Al + Mg/Si/Cu/Zn | Lightweight, corrosion resistant | 2.6–2.8 | Transport, heat exchangers |

| Copper alloys | Cu + Zn/Sn/Ni | Conductivity, corrosion resistance | 8.4–8.9 | Electrical, marine, plumbing |

| Nickel alloys | Ni + Cr/Al/Co | High-temperature strength | 8.2–8.9 | Turbines, chemical plants |

| Titanium alloys | Ti + Al/V | High strength-to-weight, corrosion resistance | 4.4–4.6 | Aerospace, medical |

(Table 1 sources: general literature and material datasheets.)

Table 2: Representative stainless steel grades and quick chemistries

| Grade | Family | Cr (%) | Ni (%) | Mo (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 304 | Austenitic | 18–20 | 8–10 | 0 | General purpose, food service |

| 316 | Austenitic | 16–18 | 10–14 | 2–3 | Better pitting resistance (marine) |

| 430 | Ferritic | 16–18 | 0–0.75 | 0 | Magnetic, less corrosion resistance |

| 17-4 PH | Precipitation-hardening | 15–17.5 | 3–5 | 0 | Heat-treatable high strength |

Table 3: Common aluminum alloy series

| Series | Principal alloying element | Typical applications |

|---|---|---|

| 1xxx | Pure Al | Electrical conductors |

| 2xxx | Cu | Aerospace structures (strength) |

| 5xxx | Mg | Marine and structural (weldable) |

| 6xxx | Mg + Si | Extrusions, general structural (6061) |

| 7xxx | Zn | High-strength aerospace (7075) |

Table 4: Typical copper-based alloys

| Alloy | Main composition | Typical property advantage | Use case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brass | Cu + Zn | Good machinability, fair corrosion resistance | Fittings, valves |

| Bronze | Cu + Sn | Improved wear resistance | Bearings, artistic castings |

| Cupronickel | Cu + Ni | Marine corrosion resistance | Heat exchangers, condenser tubes |

5. High-performance and specialty alloys

5.1 Superalloys

Nickel-base superalloys are engineered for long-term strength under creep and oxidation at high temperatures found in gas turbines. Critical alloying elements include Co, Cr, Al, Ti and minor refractory elements. Typical processing includes vacuum induction melting, directional solidification or single-crystal casting to resist creep.

5.2 Refractory alloys

Alloys based on molybdenum, tungsten, niobium or tantalum operate at extreme temperatures. They require special processing and machining methods and are used in furnaces, rocket nozzles and nuclear applications. Relevant standards and supplier datasheets define acceptable impurity levels due to their influence on ductility and recrystallization.

5.3 Corrosion-resistant nickel alloys

Hastelloy and similar compositions resist chloride, nitric and sour environments in chemical processing. Selection must include consideration of galvanic compatibility and welding metallurgy.

5.4 Biomedical titanium and cobalt-chrome alloys

Ti-6Al-4V and cobalt-chrome (CoCrMo) alloys are common in implants; biocompatibility, ion release behavior and fatigue performance direct selection. Surface finishing and sterilization compatibility are practical concerns.

6. Production methods and their effect on alloy properties

Alloy performance depends not only on composition but also on production route:

-

Casting: Good for complex shapes and high-volume parts; microstructure depends on cooling rate and inoculation. Cast irons are a typical example.

-

Wrought processing (rolling, forging, extrusion): Produces refined microstructure and directional strength; commonly used for steels, aluminum extrusions and copper products.

-

Powder metallurgy and additive manufacturing: Enable near-net shapes, tailored microstructures and complex chemistries; control of porosity and heat treatment is critical.

-

Heat treatment: Annealing, normalizing, quenching and tempering, solution treatment and ageing change phase distribution and precipitate structure, thereby tuning strength/ductility and corrosion resistance.

Processing notes:

-

Welding adds thermal cycles; filler selection and post-weld heat treatment matter for matching corrosion resistance and strength.

-

Machining hardness and work-hardening behavior influence tooling choice.

7. Key standards, testing and traceability

Standards define chemical composition ranges, mechanical test methods and acceptance criteria. For reliability and regulatory compliance, purchase specifications should reference consensus standards (ASTM, EN, ISO, SAE, UNS):

-

ASTM provides hundreds of metals standards that specify chemistries and mechanical properties for product forms and applications.

-

NIST maintains thermophysical data and vetted property datasets useful for design computations and simulations. NIST

-

ASM International and equivalent technical societies publish alloy datasheets, performance summaries and design-oriented guidance.

Traceability best practices:

-

Request mill test reports (MTR) or certificate of conformity with each heat/batch.

-

For critical components, specify independent material analysis (spectrochemical testing) and mechanical test results for acceptance.

8. Practical alloy selection checklist

When selecting an alloy for a new component, work through these items and document them in the specification.

-

Functional requirements: required strength, fatigue life, stiffness, conductivity.

-

Environment: temperature range, presence of chlorides, acids, abrasion, UV exposure.

-

Mass constraint: is minimizing weight a priority (favor aluminum, titanium, magnesium)?

-

Manufacturing method: cast, machined, welded, additive; this affects allowable chemistries and tempers.

-

Surface treatment: will plating, anodizing or coating be used? Some alloys accept coatings better than others.

-

Cost and supply: availability and cost volatility (nickel and cobalt prices can be volatile).

-

Standards and certification: regulatory constraints, required MTRs or special acceptance tests.

-

Lifecycle and recyclability: end-of-life handling, environmental restrictions (lead, cadmium restrictions).

-

Compatibility: galvanic potential relative to mating materials to avoid corrosion.

-

Testing plan: specify tensile, impact, fracture toughness and corrosion testing as needed.

9. Comparison tables — rapid lookup for engineers

Table 5: Quick physical-property comparisons (typical ranges)

| Property | Carbon steel | Stainless (300 series) | Aluminum 6061 | Copper C110 | Titanium Ti-6Al-4V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density (g/cm³) | 7.8 | 7.9 | 2.7 | 8.96 | 4.43 |

| Elastic modulus (GPa) | 200 | 200 | 69 | 120 | 115 |

| Tensile strength (MPa) | 350–700 (varies) | 500–900 | 150–350 | 200–400 | 800–1100 |

| Thermal conductivity (W/mK) | 50 | 16 | 150–170 | 380 | 7–10 |

| Corrosion resistance | Low (unless coated) | High | Good (oxidizes) | Excellent (in many) | Excellent |

Table 6: Welding considerations (general)

| Alloy family | Weldability | Typical filler approach | Post-weld treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon steels | Good | Similar composition fillers | Stress relief or tempering often recommended |

| Stainless steels | Variable | Matched or over-alloyed fillers; avoid sensitization | Solution anneal or passivation where needed |

| Aluminum | Good but hot-cracking risk | Proper Si/Mg fillers | Stress relief and solution/ageing for heat treatables |

| Nickel superalloys | Difficult | Specialized filler metals | Controlled heat treatment, often HIP for cast parts |

| Titanium | Good in controlled environment | Similar alloy fillers under inert gas | No post-weld required if processed correctly |

10. Frequently asked questions

Q1: What is the simplest way to decide between steel and aluminum for a structural part?

A1: Compare required strength-to-weight ratio, corrosion exposure and cost. If weight is critical and moderate strength suffices, aluminum often wins. For heavy loading and cost-sensitive large structures, carbon or alloy steel is usually preferred. Also check joining methods and fatigue behavior.

Q2: How does stainless steel resist corrosion?

A2: Stainless steels form a thin chromium-rich oxide film on the surface that limits further oxidation. This passive layer reforms when damaged provided sufficient chromium is present in the alloy and environmental conditions do not aggressively attack it.

Q3: Are aluminum alloys magnetic?

A3: No. Aluminum and its common alloys are nonmagnetic. This is advantageous for electronic housings and some specialty applications.

Q4: What are superalloys and when must they be used?

A4: Superalloys are specialized nickel- or cobalt-based alloys designed for high-temperature strength and oxidation resistance. Use them in turbine engines, exhaust and high-temperature chemical reactors where ordinary steels and conventional alloys fail.

Q5: Why do some alloys have many trade names?

A5: Proprietary processing, exact chemistry tweaks and supplier branding lead to many trade names. For engineering, always reference the standard number or full chemical specification rather than trade names alone.

Q6: How should I read a mill test report (MTR)?

A6: Verify heat number, chemical composition against the specified standard, mechanical test values (yield, tensile, elongation), and product form. Confirm any special heat treatments and surface condition claims.

Q7: Do all copper alloys conduct electricity equally?

A7: No. Pure copper has the best electrical conductivity; alloying reduces conductivity. Use high-purity copper for conductors; use brass or bronze when mechanical or corrosion properties matter more.

Q8: Which standards should I reference for aluminum extrusions?

A8: ASTM B221 for aluminum extruded bars, shapes and tubes and other ASTM/EN specifications depending on application and alloy choice. Always specify alloy, temper and standard in purchase orders.

Q9: How do phase diagrams help alloy selection?

A9: Phase diagrams show phase stability versus temperature and composition, informing heat treatment windows, solvus lines for precipitates and melting or solidification ranges. They are crucial for designing heat treatments and controlling microstructure.

Q10: What testing is recommended for a critical safety component?

A10: Combine mechanical testing (tensile, impact, fracture toughness), non-destructive testing (ultrasonic, radiography), metallography and chemical analysis. For extreme environments add corrosion tests and creep testing if high temperature service applies.